The world’s first biggest Lift irrigation project is ailing under the apathy of Telangana State government for violating land acquisition laws and blatantly flouted the norms causing injustice to several villagers.

Telangana’s Kaleshwaram Lift Irrigation Project has caused several rehabilitation issues for the people it has displaced, symptomatic of hardships most major large-scale irrigation projects cause in the country.

Telangana’s Kaleshwaram Lift Irrigation Project has caused several rehabilitation issues for the people it has displaced, symptomatic of hardships most major large-scale irrigation projects cause in the country.

On June 22, the Telangana high court directed district officials in the state’s Siddipet district “not to dispossess” a group of elderly people whose homes will drown under the upcoming reservoir.

The petitioners were not offered any rehabilitation or resettlement packages by the state government and were being asked to leave, despite a stay order from the court. “Your officers are acting in an egoistic manner,” the judges observed in court.

The Komaravelli Mallanasagar is among the 20 reservoirs proposed under the massive Kaleshwaram Lift Irrigation Project (KLIP) coming up in Telangana. This was not the first time the high court rapped the state over its treatment of people who would be displaced by the project.

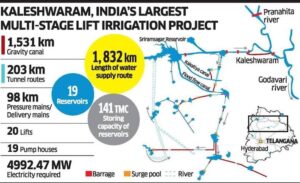

Touted as the world’s largest lift irrigation system, the Kaleshwaram project set multiple records with the world’s longest water tunnels, aqueducts, underground surge pools and biggest. The project aims to irrigate 18.26 lakh acres of land across 13 districts, provide water for industries and drinking water to Hyderabad and Secunderabad.

As per the detailed project report prepared by the state government, an area of 14,567 hectares, including private land of 12,340 hectares, will drown under the project, displacing at least 15,000 families.

In the ‘Telangana Socio Economic Outlook’ report, the Telangana Rashtra Samithi (TRS)-led state government claimed that the compensation for land acquisition had been done in accordance with the ‘law of the land’ and that rehabilitation and resettlement had been as per the Land Acquisition Act, 2013.

The ground reality paints a different picture. Land conflicts have erupted over at least five of the project’s reservoirs after villagers opposed the manner in which the state government bypassed and violated the 2013 law, according to data from Land Conflict Watch, a database of ongoing land conflicts in India.

The state government also released waters before all the people could move out and forcefully evicted them in midnight operations in April 2020, during the strict COVID-19 lockdown.

Since 2018, the Telangana high court has been hearing over a hundred pleas filed by affected families, including elderly citizens and unmarried adults who have been left out of rehabilitation schemes. The court has accused the state of “coercing” people into giving up their land, has imposed fines on government officials and even sentenced a district collector to jail.

Since 2018, the Telangana high court has been hearing over a hundred pleas filed by affected families, including elderly citizens and unmarried adults who have been left out of rehabilitation schemes. The court has accused the state of “coercing” people into giving up their land, has imposed fines on government officials and even sentenced a district collector to jail.

Experts say the KLIP is becoming an example of how large-scale irrigation and water supply projects end up being unfair to those who are displaced from their homes and lands, and also how such projects are stalled in courts when governments use controversial land acquisition practices and violate acquisition laws.

This affects the people involved and causes project costs to skyrocket – from an initial estimate of Rs 40,000 crore, the KLIS budget increased to Rs 88,000 crore by 2020 and is now expected to cost over Rs 1.15 lakh crore due to delays.

“Six people who opposed forceful evictions or demanded more compensation have died by suicide but the TRS did not even acknowledge the deaths,” said T. Sagar, general secretary of the Telangana Rythu Samithi, the state unit of the All India Kisan Sabha.

“Despite the progressive provisions of the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013 (LARR), the case of the Kaleshwaram project has only become a part of the larger trend of unfulfilled promises,” said Madhuresh Kumar of the National Alliance of People’s Movements (NAPM), an umbrella organisation of rights groups and movements from across the country.

Telangana government officials in the irrigation department and the chief minister’s office did not respond to phone calls and emails with queries on these allegations.

The Kaleshwaram project is a network of reservoirs, canals and pump houses that will pump water from the Godavari river uphill into Telangana. The reservoirs will submerge 14,567 hectares of land, 85% of which are farmlands and homes owned by individuals.

In such cases, the government has to acquire land under the LARR.

The LARR, which came into force on January 1, 2014, mandates that the government carry out social impact assessments (SIA) to understand the extent of the displacement that will be caused by a project, pay landowners at least two times the market price for their land and ensure the rehabilitation and resettlement of everyone who was displaced.

In July 2015, the state government issued Government Order (GO) 123, which enabled the government to carry out what it called “voluntary acquisition” of land from “willing” landowners. It would purchase the land directly from landowners at a negotiated price but without following any of the compensation and rehabilitation requirements under the LARR.

In July 2015, the state government issued Government Order (GO) 123, which enabled the government to carry out what it called “voluntary acquisition” of land from “willing” landowners. It would purchase the land directly from landowners at a negotiated price but without following any of the compensation and rehabilitation requirements under the LARR.

It began purchasing land across the state for the KLIS under GO 123 instead of the LARR.

The move ran into opposition from villagers affected by projects like the Annapurna reservoir, which will submerge three villages in the Siddipet district. In 2016, the district administration published notifications in local newspapers saying that it had received consent from landowners in the area. However, in a petition filed before the Telangana high court, the people claimed they were approached by the government after the notification had been published. They were told that since their lands would be submerged under the reservoir, they had “no choice but to surrender their lands” at a fixed rate of Rs 6 lakh per acre, according to their submission recorded by the high court.

The government then imposed a curfew and “forced” landowners to sign sale deeds written in English, which they did not understand. In its counter-affidavits, the state government did not deny these allegations.

In January 2017, the high court struck down GO 123 following a petition by people affected by the Kondapochamma reservoir of the KLIS, but the state government had amended the LARR in 2016. The amended Act received the president of India assent’s on May 12, 2017. The amended law says that compensation, rehabilitation and resettlement entitlements can be negotiated with landowners.

Further, it does not require SIAs and, unlike the central Act, the state amendment allows the government to retain the land for as long as it takes to set up the project.

On April 9, 2019, the high court granted a stay on the land acquisition after a petition was filed by 11 families. They said that, after the preliminary notification of acquisition in 2017, the government did not make a declaration under Section 19 (1) of the LARR (Telangana Amendment) Act. As per Section 19 (7), if no declaration is made within 12 months, the preliminary notification would be deemed cancelled, unless the government issues an extension to the deadline. The 12-month deadline had ended on December 27, 2018 and the government had extended it by two months to February 28, 2019.

When the villagers filed a petition against the extension, the Telangana high court stayed the order.

In March 2020, officials released Godavari water into the Ananthagiri reservoir on a trial basis from one pump. In April 2020, in the midst of the nationwide COVID-19 lockdown, villagers were evicted and forced to move into a Rehabilitation and Resettlement (R&R) colony in Ranganayaka Puram.

In March 2020, officials released Godavari water into the Ananthagiri reservoir on a trial basis from one pump. In April 2020, in the midst of the nationwide COVID-19 lockdown, villagers were evicted and forced to move into a Rehabilitation and Resettlement (R&R) colony in Ranganayaka Puram.

People affected by the Kondapochamma reservoir met a similar fate. In April, 2020, the state government stated that the construction of the reservoir was complete and claimed that the residents of the submerging villages (Bailampur, Thanedar Palli, Mamidyala and Thanedar Palli) had been moved to the new R&R colony at Tunki Bollaram village and that 35 families that did not want to shift were given plots to construct their own houses.

On April 30, 2020, villagers were evicted and shifted into tin sheds. On May 7, 2020, the high court directed the district collector to shift the evicted villagers to two-bedroom houses in Gajwel immediately. On May 29, 2020 the reservoir was inaugurated.

In July 2020, the high court held that the state government “coerced” the villagers affected by Kondapochamma and Ananthagiri reservoirs to sell their lands at low rates and that the petitioners were eligible for compensation and rehabilitation as per the LARR Act, 2013.

Farmers organisations allege that the failure to conduct SIAs for the project has eventually left thousands of landless agricultural labourers with no compensation, effectively taking away their rights granted under the LARR Act.

“As SIAs are not conducted, no compensation was given or promised to the agriculture labourers who were earlier dependent on the farm lands taken away for the project. This has left them with no other option but to migrate to other regions in search of livelihood,” said Vemalapalli Venkataramaiah, president of All India Kisan Mazdoor Sangh (AIKMS), a national farmers’ union.

C.H. Ravi Kumar, one of the counsels representing the affected people in the high court, says that there are around 300 families who have filed writ petitions against compensation or rehabilitation, including landless agricultural labourers who would lose their livelihoods.

Kumar said that since the land acquisition process began, “the government’s stand has been clear; R&R packages were promised only to families who parted with both their houses and lands. In the case of farmers whose agricultural land is acquired, the authorities have offered only monetary compensation without giving R&R package. For landless labourers, no compensation was announced, forcing them to migrate to other regions in search of work.”

He added that there is enormous dissent among those families who were offered R&R packages as there are differences in the eligibility criteria among unmarried majors, married people and senior citizens.

He added that there is enormous dissent among those families who were offered R&R packages as there are differences in the eligibility criteria among unmarried majors, married people and senior citizens.

In April 2019, the Telangana government had issued GO 78, which reduced the rehabilitation benefits that were legally required by the LARR. The order laid down differential compensation entitlements to married and unmarried adults. Unmarried adults would receive only Rs 5 lakh and a 250 square-yard plot while the former were offered Rs 7.5 lakh and a double bedroom house on a 250 square-yard land as the rehabilitation entitlement. Single individuals over the age of 65 years from Mallannasagar and Ananthagiri reservoir were not eligible for any rehabilitation benefits.

In case of the Gouravelli reservoir, unmarried adults were entitled to receive Rs 2 lakh instead of Rs 5 lakh under the GO. This led to the youth in the village to object to the package since the youth in other KLIP-affected villages (like Mamidyala) were getting Rs 7.5 lakh and a 2BHK house on a 250 square-yard plot.

In 2019, 24 unmarried adults from the Mamidyala village challenged the GO in the high court as being discriminatory. In September, 2020, the high court directed the state to give them the same benefits and imposed costs of Rs 5,000, payable by the state government to each petitioner. It struck down GO 78, calling it “arbitrary, illegal and violative of Article 14 of the Constitution” and provisions of the LARR.

Venkataramiah noted that, in projects where large scale private land is to be acquired, authorities’ foremost priority would be to award contracts for various works under the project. “Land acquisition starts after that and R&R becomes the least priority. Similar has been the case in the KLIS project,” he said.

“There are also cases where the oustees are paid more compensation in villages falling under the constituency of the then-irrigation minister Harish Rao,” said farmers’ leader Sagar.

The controversy over the displacement caused by KLIS has continued.

On March 9, 2021, the high court awarded a three-month jail term to Siddipet district collector P. Venkatarama Reddy and a four-month jail term to Jayachandra Reddy, the special deputy collector, Kaleshwaram land acquisition, for being in contempt of the court’s orders in cases related to land acquisition for the Mallannasagar reservoir.

On March 16, 2021, the Supreme Court set aside the July 2020 judgement of the Telangana high court, saying the court had not heard arguments from both sides and remanded the matter to the state high court for fresh adjudication. The case is still pending in the high court.

Meanwhile, the project has also run into trouble over environmental and water-related approvals. In October 2020, the National Green Tribunal declared the project’s environmental clearance as void. This was because the project’s capacity was increased to pump three thousand million cubic feet (TMC) of water per day – up from two TMC per day – and this would require major changes to the original project, involving the taking over of large tracts of land and the building of massive infrastructure that could harm the environment.

The Telangana government argued that the expansion did not require infrastructural changes and hence does not require fresh clearance. The NGT disagreed and directed the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) to constitute an expert committee to assess the environmental damages that would be caused by the project if it ran without clearance. On June 18, 2021, the NGT granted a three-month extension to the committee for submitting its report.

The rehabilitation issues with the KLIS project are symptomatic of the difficulties caused by many large-scale irrigation projects, where thousands are set to be displaced but the government fails to rehabilitate everyone. Eventually, the project was commissioned with many still unrehabilitated.

There are at least 39 active land conflicts over irrigation projects across India, affecting 5.3 lakh people, 6,386 square km of land and about Rs 79,000 crore of investment, according to the Land Conflict Watch database. Another 3.8 lakh people and 1,639 sq km land is in land conflicts over multipurpose dams, the database shows.

The non-implementation of R&R promises has been one of the persisting issues with development projects in India, said Madhuresh Kumar. “Especially, irrigation projects have caused the biggest displacements in independent India,” he said.

Project-affected people in Bhakra Nangal dam, Hirakud dam and the Sardar Sarovar projects are awaiting compensation against displacement for some decades, Kumar said.

For example, after a decades-long land conflict, the Sardar Sarovar Dam project on the Narmada was filled to its full capacity in 2019, even when thousands were still living in its submergence areas and had to be hastily evacuated.

While the central land acquisition law, enacted in 2014, was supposed to make compensation and rehabilitation fair and transparent for land losers, the KLIS project shows how, in reality, the law gets diluted and violated by state governments. #KhabarLive #hydnews