Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister Chandrababu Naidu asked people to donate e-bricks, each costing Rs 10, for construction of Amaravati. The challenge now is to turn virtual reality into reality.

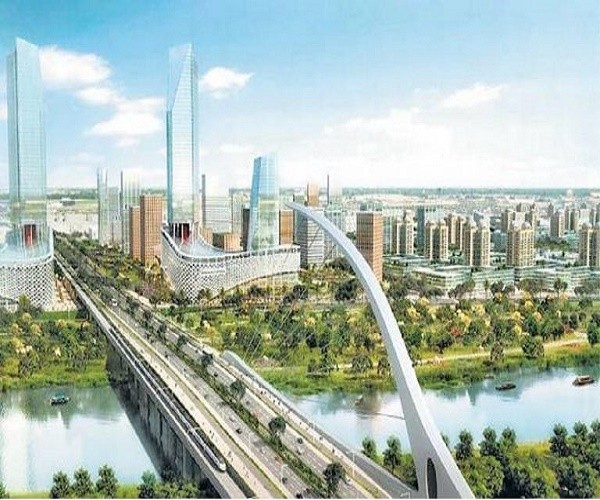

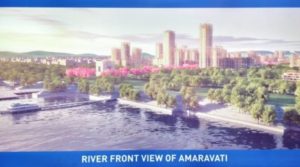

The design for what Amaravati will look like, along the banks of the river Krishna

The first phase of the dream capital city of Andhra Pradesh will be complete by the end of 2018, it is hoped. But delays, doubts & fears hang like a cloud.

Construction work on Andhra Pradesh’s new capital Amaravati has finally begun, and officials say the first phase of Chief Minister Chandrababu Naidu’s dream project will be complete by the end of this year.

Spread across 53,000 acres of land, Amaravati is being built virtually from scratch. Inspired by what looks like a mix of Singapore and cities that feature in sci-fi films, Naidu says he aims to make it the most “futuristic” capital city in the world.

The master plan includes a government complex modelled on New York’s Central Park, 27 townships, navigable waterways and nine themed “mini-cities”. It is projected to house 3.5 million people by 2050.

However, that vision has only just began to take shape. As ThePrint reported previously, Amaravati has been battling problems over design, environmental clearances and acquisition of 33,500 acres of land through a unique land-pooling scheme.

However, that vision has only just began to take shape. As ThePrint reported previously, Amaravati has been battling problems over design, environmental clearances and acquisition of 33,500 acres of land through a unique land-pooling scheme.

Announced on 1 January 2015, Amaravati has been designed by the high-profile architect Norman Foster, of Foster + Partners, after researching and analysing cities and countries around the world, most notably Singapore.

Engineering and design are complete, and physical construction has begun. The Singaporean firms Ascendas-Singbridge Pvt. Ltd. and SembCorp Development Pvt. Ltd. have been given the rights to construct. Over the last three years and four months, 95 percent of the land required for the project has been acquired.

The city aims to be completely environment friendly, and will be powered by solar energy. Traffic and vehicular pollution will be minimised through a “5-10-15” rule used in the city’s design — from any given house, all necessary and emergency services such hospitals and schools will be a 5-minute walk; open and recreational spaces will be a 10-minute walk; and work will be a 15-minute walk.

The Commissioner of the Andhra Pradesh Capital Region Development Authority (APCRDA), Dr Sreedhar Cherukuri, says 53 percent of the first phase of the project is complete. Phase I includes government housing and basic infrastructure such as roads and power supply, and will cost around Rs 50,000 crore.

The Commissioner of the Andhra Pradesh Capital Region Development Authority (APCRDA), Dr Sreedhar Cherukuri, says 53 percent of the first phase of the project is complete. Phase I includes government housing and basic infrastructure such as roads and power supply, and will cost around Rs 50,000 crore.

The entire city is expected to cost Rs 1 lakh crore to build, Cherukuri says.

The project’s promoters claim Amaravati will be one of the “happiest” cities in the world. The city hosted the Happy Cities Summit, an international conference on urban innovation and happiness, from 10-13 April. Naidu inaugurated the three-day summit attended by delegates from across the globe, including Finland and Bhutan, considered two of the happiest countries in the world.

“Make Amaravati your second home,” Naidu urged the participants, adding that the Andhra Pradesh government aims to use technology to enable participative governance and sustainable living to ensure a high happiness quotient.

A visit to the construction sites shows that while work has begun, not much has been accomplished yet, particularly in view of the project deadline of February 2019.

Construction work on government housing complexes — to be built using the ‘shear wall’ technology, which does not use bricks — has only just begun, but APCRDA says all complexes will be ready by the end of this year.

Construction work on government housing complexes — to be built using the ‘shear wall’ technology, which does not use bricks — has only just begun, but APCRDA says all complexes will be ready by the end of this year.

In all, 3,840 apartments will be built by the end of 2018, according to Zachariah Madasu, the chief engineer for Housing & Building at APCRDA

APCRDA claims work on all the other parts of Amaravati has also begun, although the only structure standing is the temporary secretariat, from which the Andhra government has been functioning since 2015. The building was constructed in a record 139 days.

Although the project has been publicised as a marvel of sustainable engineering and design, local activists have raised concerns about its ecological viability.

Anumolu Gandhi, a local farmer and activist, says the land Amaravati will occupy is prone to floods. The city will be built on existing floodplains, setting the stage for future disasters, he fears.

The area has flooded twice in the last 20 years. In 2009, roughly 29,000 acres of the 53,000 acres going towards Amaravati’s development were flooded by the Kondaveeti Vagu, a tributary of the Krishna river.

APCRDA says it has taken measures to protect the region from floods by introducing a “lifting scheme” — Kondaveeti Vagu will be widened, and four reservoirs will be built to avoid flash-floods.

Cheruku, the commissioner, said the National Green Tribunal has reviewed the entire project and given it a green signal. “The city is completely floodproof,” he says.

Last year, 45 Indian cities competed to find a place in the final list of 30 that would be developed as smart cities. Much to everyone’s surprise, Amaravati, the proposed capital city of Andhra Pradesh made it to the list, at fourth position. What’s more, Amaravati beat cities like Puducherry, Bengaluru and Gandhinagar in the race.

A mirage called Amaravati had trumped real cities, just because it had a smarter plan on paper. Even Telugu Desam leaders couldn’t stop sniggering, pointing out that Amaravati did not even have two new buildings in the 16.9 sq km core capital zone.

This, in a nutshell, is the story of Amaravati. An ultra-modern city spread over 54,000 acres that aspires to be one of the best five in the world, exists at the moment only in glitzy PowerPoint presentations that Andhra chief minister Chandrababu Naidu loves to make.

This, in a nutshell, is the story of Amaravati. An ultra-modern city spread over 54,000 acres that aspires to be one of the best five in the world, exists at the moment only in glitzy PowerPoint presentations that Andhra chief minister Chandrababu Naidu loves to make.

Nearly four years after Naidu came to power and more than two years after Prime Minister Narendra Modi laid the foundation stone for the project, no significant brick and mortar work has begun. Naidu, government officials and consultants were globe-trotting till late last year to finalise the designs. The tenders for the main two iconic buildings — the Andhra assembly and the high court, will be floated only in May 2018. The delay was because initial designs by a Japanese firm in 2016, made the state assembly building look like an atomic reactor and was widely lampooned by citizens. Initial work has started only on constructing 4,000 houses for government employees.

The rejected initial design for the assembly building, which looked like an atomic reactor. Photo from Andhra Pradesh government. In his first innings as chief minister, Naidu enjoyed the tag of ‘CEO of AP Inc.’ — something that fawning industrialists bestowed on him. Naidu 2.0 wants to better that and go down in history as the visionary creator, not merely as an efficient manager, of Amaravati. But with little money coming from New Delhi to fund Naidu’s Neverland, it risks becoming a fictional faraway dream.

For Naidu, Amaravati is a heady mix of history and culture with 21st century modernity. Amaravati was the ancient seat of power of the Satavahana rulers and the mythical city of Lord Indra, the king of Gods. The name was adopted for the capital by the religiously inclined, grandeur-obsessed Naidu.

This is perhaps why Baahubali movie director S.S. Rajamouli, known for creating the fictional kingdom of Mahishmati in his magnum opus, was roped in by Naidu to brainstorm about the capital with British architectural firm, Norman Foster & Partners. Everything about Amaravati will be grand and larger-than-life. Even the budget to build the city is a mammoth Rs 50,000 crore.

But not just empty grandeur, Naidu wants Amaravati to be smart too — with no overhead power wires, piped gas to every house, smart metres for power, world-class roads, waterfronts, electric cars and adequate green lung space. The focus is on quality of life for residents and an experiential treat for tourists. He calls it the People’s Capital.

The new design for the Assembly Building | Photo from Andhra Pradesh government.

But the Sivaramakrishnan committee, appointed by the central government in 2014 to suggest where the new capital of Andhra could come up, had recommended a decentralised capital, instead of one omnibus centre. But Naidu chose to ignore its suggestions. He is committing the same blunder he made in Hyderabad when he was chief minister between 1995 and 2004 — ie., to develop only Hyderabad, ignoring other urban clusters in Andhra.

When bifurcation took place in 2014, the realisation dawned on the Visakhapatnams and the Vijayawadas that they were not a patch on Hyderabad while Telangana walked away with the advantage of a developed capital city. But a decade later, Naidu is once again putting all his eggs in the Amaravati basket.

When bifurcation took place in 2014, the realisation dawned on the Visakhapatnams and the Vijayawadas that they were not a patch on Hyderabad while Telangana walked away with the advantage of a developed capital city. But a decade later, Naidu is once again putting all his eggs in the Amaravati basket.

The dream project can turn into a nightmare if Naidu does not return to power in 2019. The investors are already worried, and many national and international hotel chains, entertainment majors, IT companies have postponed their decision to set up shop in Amaravati to mid-2019. By that time, elections to the Andhra assembly would be over and there will be clarity for the next five years.

But this wait and watch attitude is affecting Brand Amaravati. Its link to the political fortunes of one man makes its future tense. Unless economic activity takes off in Amaravati, land value will not increase. This will mean Andhra will find it tough to repay the Rs 7,500 crore loan it has taken from HUDCO and Rs 4,000 crore from the World Bank. It will mean farmers who agreed to land pooling in the hope that they can sell their developed land at a higher price, will not get big money. It will also mean the 4,000 acres of prime land that Naidu plans to leave untouched to sell later to raise funds, will not fetch the price he dreams of.

The main opposition party, the YSR Congress, has never been in favour of converting the fertile plains along the Krishna into a concrete jungle. If Jaganmohan Reddy comes to power, he may not want to continue with a project where the credit eventually will go to his bete noire Naidu.

There are environmental concerns too. The go-ahead from the National Green Tribunal in November 2017 came with a rider, asking the government not to clear land in the project area without environmental clearance. Environmentalists have protested that an impartial and comprehensive environmental assessment has not been done to study the effect of this large-scale urbanisation on wetlands and fertile agricultural land. Those who oppose Amaravati claim that while Naidu may wow the ignorant with fancy designs, future generations may end up bearing the consequences of this man-made disaster built on fertile land that grew three crops in a year.

True to his hi-tech image, Naidu asked people to donate e-bricks to the construction of Amaravati, each brick costing Rs 10. The challenge now is to convert the virtual reality into reality, brick by brick. #KhabarLive